If you’re like me, you may be tired of hearing about the election. It seems that everything we see on TV or online nowadays is a political ad, trying to get us to vote one way or another. For me, it seems that every single ad I see on YouTube is from someone either reminding me to vote or getting me to vote for a certain candidate (from both sides). While I understand why these ads are important, the seemingly constant deluge of information has me feeling like this:

When I first considered writing this series, I thought about what I felt were some of the murkier parts of our election system. The first thing that came to mind was the electoral college. By now, many people are likely aware that it exists, but some of the finer points of how it works may be a little harder to understand. That said, with only three Mondays left until the 2020 election, let’s take a deeper dive into the US electoral college together.

What is the Electoral College?

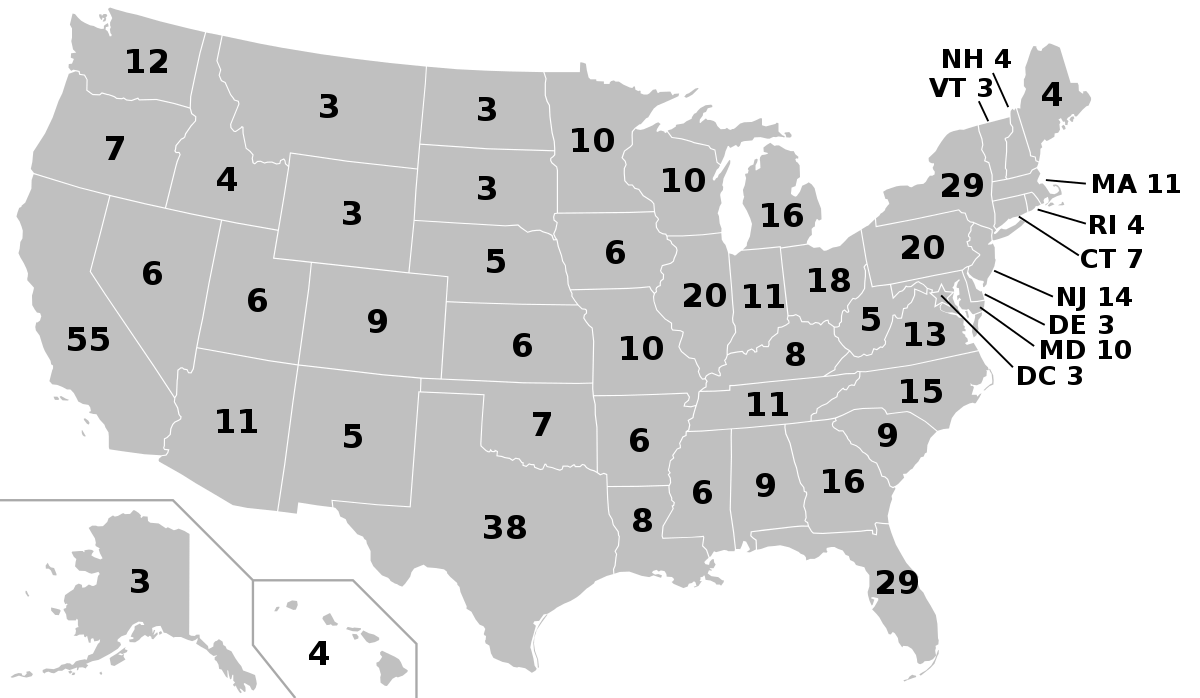

Although most local, state, and federal elections are decided by a popular vote, the US presidential and vice-presidential elections are not. Instead, a group of 538 electors, distributed across the 50 states and Washington, D.C., are chosen to represent the voters in each state. These electors are chosen by their individual political parties and are often either politicians themselves or have close ties to a party’s nominee. Each state gets the same number of electors as it has congressional representatives. Let’s use Tennessee as an example (mainly because I grew up there and am most familiar with its political system). Tennessee, like every other state, has two senators. It also has nine state representatives. This means Tennessee has a total of 11 electors. This number is subject to change, as the number of state representatives a state has is based on its population. So, in theory, if Tennessee’s population were to suddenly increase a substantial amount, they would get more state representatives and therefore more electors (although this is highly unlikely).

How does the Electoral College work?

When we cast our votes for president and vice president, we are actually casting our votes for electors. In 48 states and Washington, D.C., whichever candidate wins the popular vote gets all of the electors for that state. The exceptions are Maine and Nebraska, which designate electors based on a proportion of votes. In these states, the winner of the popular vote gets two electoral votes, and the winners of the congressional districts get one. While this means the states can give electoral votes to multiple candidates, they can still give all of them to the same candidate if the congressional district winners align with the state popular vote. In order to win, a candidate must receive a majority of the votes, or a minimum of 270.

Using the 2016 election as an example, President Trump won the popular vote for Tennessee, and therefore received all of the electoral votes for the state. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, won the popular vote for California, so she received all of their electoral votes. While most states, pledged their electoral votes to the winner of the state’s popular vote, there were a few cases of “faithless electors”, or electors who did not vote as they had originally promised. While some states have laws to prevent this (which were deemed Constitutional in 2020), not every state requires their electors to vote according to the popular vote. However, since the electoral college was established, over 99% of electors have voted as pledged.

The existence of the electoral college also means that even if a candidate wins the national popular vote, it is still possible for them to lose the electoral vote. This has happened five times: three times during the 1800s, in the 2000 election, and in the 2016 election.

What timeline does the Electoral College opperate on?

So now that we know more about how the electoral college works, let’s look at their election timeline.

November 3, 2020: US General Election Day

Mid-November through December 14, 2020: State governors prepare seven Certificates of Ascertainment. The governor will send one of these certificates to the Archivist as soon as the state’s election results are certified. Electors must be validated by December 8, 2020.

December 14, 2020: Electors Vote in their states, recording their votes on six Certificates of Vote, each of which is paired with one of the remaining Certificates of Ascertainment. Together, these form electoral votes, which are signed, sealed, certified, and sent to Congress.

December 23, 2020: The electoral votes must be received by the President of the Senate (the US Vice President) and the Archivist no later than this day.

On or before January 3, 2021: The Archivist will send the sets of electoral votes to the newly assembled Congress.

January 6, 2021: Congress counts the electoral votes. If no presidential candidate receives 270 electoral votes, the House of Representatives votes, by state (with each state having one vote), for the new president. Washington, D.C., does not get any votes because it has no representatives in the House. If no vice-presidential candidate receives 270 electoral votes, the Senate decides on the new vice president by a majority vote, with each senator having one vote.

January 20, 2021: Inauguration Day

So there you have it folks: the electoral college. While I personally believe the electoral college adds a certain layer of confusion to the whole voting process, our system was established in the Constitution over 200 years ago, and it would take a new Constitutional Amendment to change the process. With everything that’s going on with this year’s election, I think it’s more important than ever to understand how our system works, so I hope this was helpful. Stay tuned for the next installment in Understanding the US Election System: Battleground States.

Source: The National Archives